It’s time for moving media literacy to the tipping point!

OCTOBER 14, 2019: Read the House of Representatives Bill Here. Thanks to Representative Jim Langevin (D-RI) who sponsored the the House version of the Digital Citizenship and Media Literacy bill.

Disinformation and election propaganda are already disfiguring the media ecosystem again, far in advance of the 2020 election. Today we learned about the heinous video showed at a Trump election event in Florida, which offers a cartoonish display of gruesome violence as President Trump kills his “enemies,” the courageous journalists from a wide range of news organizations who report on his administration. Designed to appeal to teenage boys, the video may inspire violence against journalists and must certainly be recognized as harmful political propaganda.

There’s never been a more urgent time to advance media literacy and digital citizenship in American schools. School leaders understand that this generation of children and adolescents need repeated, frequent opportunities to learn how to ask critical questions about what they read, watch, see, play, use and create. Learning to recognize and resist propaganda and disinformation is an essential dimension of education in a digital age. This bill will help American educators to bring these practical and necessary real-world competencies to children in all 50 states. Parents can see from direct experience that when education is responsive to the real world that students inhabit, children and teens respond with intellectual curiosity and increased motivation. I commend the members of Congress who, with this bill, are helping address the problem of disinformation and propaganda using the power of education.

Media literacy is the only long-term strategy that embodies our country’s vital democratic traditions of robust dialogue and debate in the marketplace of ideas. When U.S. Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) introduced new legislation to combat foreign interference campaigns by improving media literacy education that teaches students skills to identify misinformation online, she certainly got my attention. After all, I’ve been complaining for months to anyone that would listen that we’re approaching the 2020 election with American teachers woefully underprepared for helping students recognize and resist the new forms of disinformation and misinformation they are likely to encounter as part of the political process.

There are certain times when a big push can make a big difference. Now is one of those times. Back in 2008, when social media was new, I was lucky enough to be able to help develop curriculum materials for teaching media literacy in the context of the first social media election. PBS had decided to make a big push to help American teachers understand this new form of expression and communication by considering its relevance to the elections. Our curriculum, called Access Analyze, Act: A Blueprint for Civic Engagement was a set of 11 lessons for teachers who were just beginning to understand how participatory culture was changing the nature of the election process. The charming (Flash-based) website which accompanied this resource has long been scrapped, of course. It’s out of date as a result of the huge changes underway as a result of the rise of digital advertising and the growing economic power of the platforms. But the curriculum got used by thousands of educators. Why? Dedicated teachers experienced the deep gap between typical instructional practices they were using and what their students actually needed to know and be able to do. They felt a social responsibility to make changes in instruction. They realized by making these changes in what and how they taught, they could help young people develop citizenship skills needed for this fast-changing digital society.

There are certain times when a big push can make a big difference. Now is one of those times. Back in 2008, when social media was new, I was lucky enough to be able to help develop curriculum materials for teaching media literacy in the context of the first social media election. PBS had decided to make a big push to help American teachers understand this new form of expression and communication by considering its relevance to the elections. Our curriculum, called Access Analyze, Act: A Blueprint for Civic Engagement was a set of 11 lessons for teachers who were just beginning to understand how participatory culture was changing the nature of the election process. The charming (Flash-based) website which accompanied this resource has long been scrapped, of course. It’s out of date as a result of the huge changes underway as a result of the rise of digital advertising and the growing economic power of the platforms. But the curriculum got used by thousands of educators. Why? Dedicated teachers experienced the deep gap between typical instructional practices they were using and what their students actually needed to know and be able to do. They felt a social responsibility to make changes in instruction. They realized by making these changes in what and how they taught, they could help young people develop citizenship skills needed for this fast-changing digital society.

Since then, many teachers have leaped to the challenge of developing their own knowledge and digital competencies, of course, in order to meet the needs of their students. We met some of these amazing educators at the 7th annual Summer Institute in Digital Literacy just last week.

But to scale this kind of training and support to reach all elementary and secondary teachers, we need the Digital Citizenship and Media Literacy Act. The act establishes a grant program at the Department of Education to help develop digital citizenship and media literacy education across grades K-12. It’s not brain surgery to make sure Americans possess the skills they need to make informed decisions about media content. In fact, it’s a form of empowerment that children and young people find fascinating.

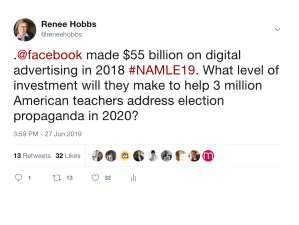

I’m grateful for Klobuchar’s leadership on this important topic. When the European Commission stepped up to help the 28 member states advance media literacy education, they were able to accomplish far more than any single nation could have done on their own. And while I believe that the media industry has an important role to play in advancing media literacy, educators shouldn’t have to rely on a handout from the platform companies, since they will never be able to help students and teachers develop a genuinely critical perspective on their role in monetizing platforms that make information warfare so very profitable.

But the work goes beyond merely dumping lesson plans into teacher mailboxes. Media literacy education requires a pedagogy of inquiry that engages young people in making key connections between the classroom and the living room. It takes practice and support to learn to teach media literacy well.

This bill could go a long way to advancing programs in media literacy that benefit American children and teens. The bill, co-sponsored by Senators Tina Smith (D-MN), Michael Bennet (D-CO), Gary Peters (D-MI), Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), and Sherrod Brown (D-OH), calls for a Department of Education grant program that would help states develop media literacy education and fund existing initiatives across grades K-12. The grant program would be available on a state and local level to develop state-wide media literacy education guidelines, incorporate media literacy into curricula, hire educators experienced with media literacy, and promote educator professional development in media literacy. The legislation would authorize $20 million in grant funding for the program. Additional support from federal agencies will be needed to ensure that the research support is available in order that best practices be identified, tracked and measured with integrity.

As I have discovered through my work in well over 200 schools and school districts, media literacy education appeals to citizens on all sides of the political spectrum. We must come together in a crisis. In teaching undergraduate students, I see how the lack of media literacy in their K-12 education puts them at a severe disadvantage in terms of making sense of their information environments. Students need support to identify, evaluate and assess political disinformation campaigns. Indeed, many of my own undergraduate students were tricked by the Blacktivist Facebook profile in 2016, which offered snappy memes targeting African-Americans in order to discourage them from voting. Blacktivist was one of the campaigns developed by Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA), whose propaganda was spread through Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter campaigns that reached 126 million users in the United States.

We are about to face a barrage of highly personalized propaganda again in just a few short months. Young Americans need skills to distinguish truth from fiction and empower them to make informed decisions about the news and politics. With the Russian propaganda machine racheting up already and with U.S. political actors of all kinds producing deepfakes, smear campaigns and all manner of fake news, the handwriting on the wall is obvious. Adversaries from both outside and inside the U.S. are targeting our democracy with sophisticated information campaigns designed to divide Americans and undermine our political system.

It’s time to fight back with education. Media literacy is one important low-cost solution that doesn’t use censorship or content moderation or regulation. It’s respectful of the robust interchange of ideas, which is fundamental to the democratic process. It can be taught at every level from grade school to grad school. And when done well, it advances traditional print literacy competencies, too.

Think of it this way: lack of knowledge about the new political economy of the Internet and the lack of critical thinking skills about media messages got us into this mess. Making those things a high priority again can get us out of it.

Pingback: Media Literacy as a SHIELD | Renee Hobbs at the Media Education Lab